Something weird is happening in America. GDP growth for Q3 was just revised up from an already scorching 4.9 per cent to 5.2 per cent, more Americans have jobs than at any time in history, but the public is up in arms about economic conditions, with consumer confidence dropping to a six-month low. There really is no pleasing some people.

With headline indicators in such rude health, we would expect the number of Americans who think they’re better off than this time last year to outnumber those who say they’re worse off by about 25 percentage points. Instead, the reportedly worse-offs outnumber the better-offs by ten points in the latest University of Michigan’s index of Current Economic Conditions.

I know what you’re thinking: inflation explains all of this. People really hate rising prices, and are reminded of them every time they buy something. Inflation’s salience drowns out other more distant or intangible gains. It’s certainly a good theory, but countries all around the world have faced steep inflation. Many steeper than the US. Presumably their consumers are also much more pessimistic than we would expect?

Well, no actually. Extending an original analysis by X user Quantian1, I have calculated expected consumer sentiment for a set of countries based on their underlying economic indicators, and compared it to actual sentiment. Relative to the eve of the pandemic, US consumers now appear gloomier than the French, the Germans and even the British. The Europeans all feel about as confident as one might expect based on how their economies are performing. Disproportionate doom seems to be a new American affliction.

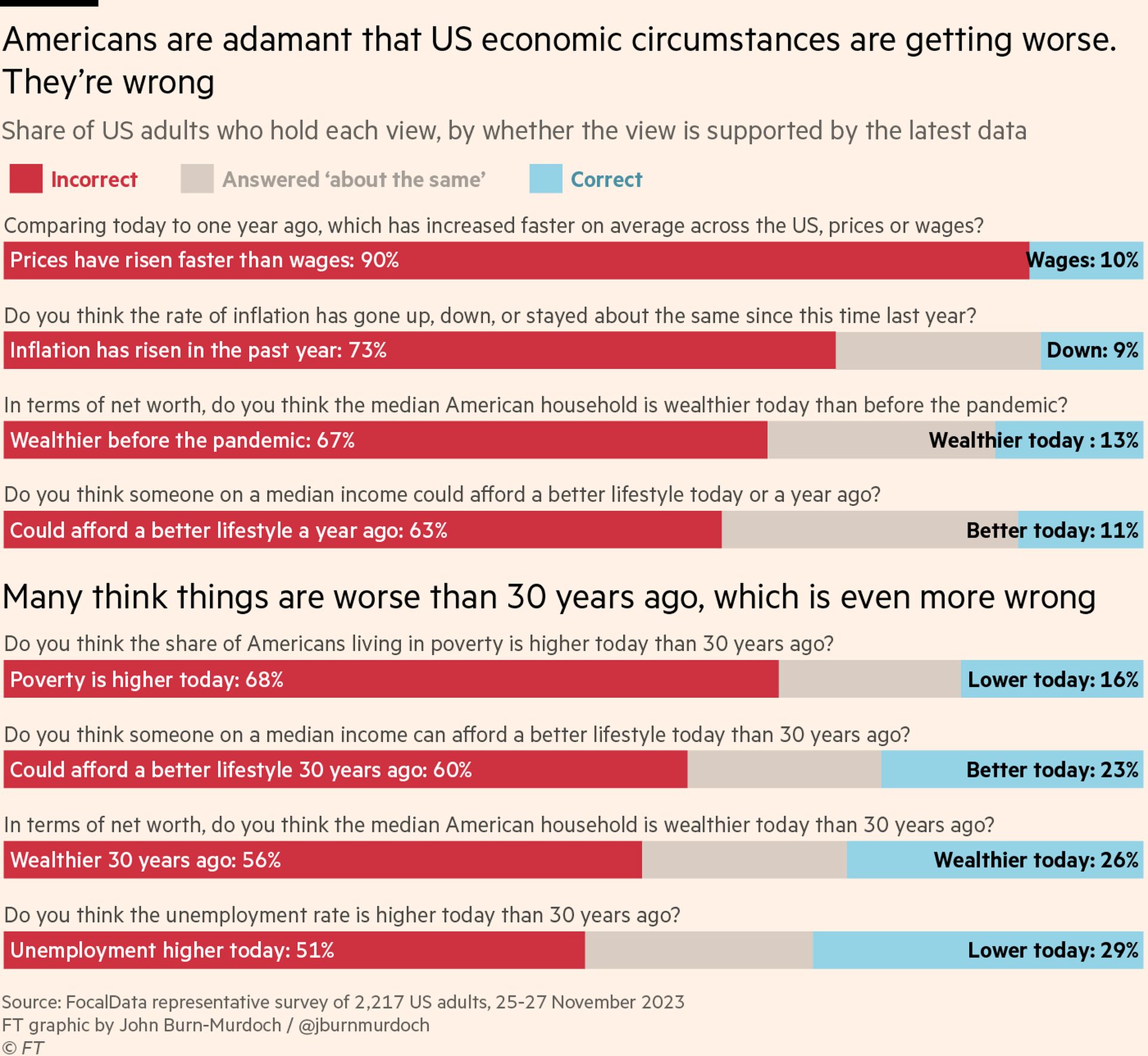

So what’s going on? Last weekend FocalData ran a poll for me, asking a representative sample of 2,000 US adults whether they thought economic circumstances had improved or deteriorated over recent years. The results were startling: Americans are consistently wrong in the negative direction on almost every measure we polled. By huge margins, they believe inflation is still rising (it’s falling), that it has outstripped wage growth (wages have outpaced prices), and that they have become less wealthy (they’ve become much wealthier).

Attempts to justify this sense of gloom often emphasise the challenges faced by less prosperous groups, but this also goes counter to the evidence. One explanation I heard is that the despondency comes from young people struggling with runaway rents. But wages have risen faster for them than the old, outpacing rents. Plus young consumers are the most positive, per the Michigan survey.

Similarly, wages have risen faster for those on the lowest incomes, reversing more than a third of the increase in wage inequality over the past four decades. Wealth has risen for the least and most wealthy alike.

The most striking response from our survey concerned the sense of longer-term progress. Large majorities of Americans think the median income today pays for a worse lifestyle than 30 years ago (demonstrably false), and that poverty is higher than it was a generation ago (it has plummeted). One particularly revealing statistic is that Americans’ assessment of their own financial situation has barely budged over the past five years, but their rating of the national economy has worsened steeply. It seems they have decided that the vibes are bad, so things must be going badly for most other people, even if not for themselves.

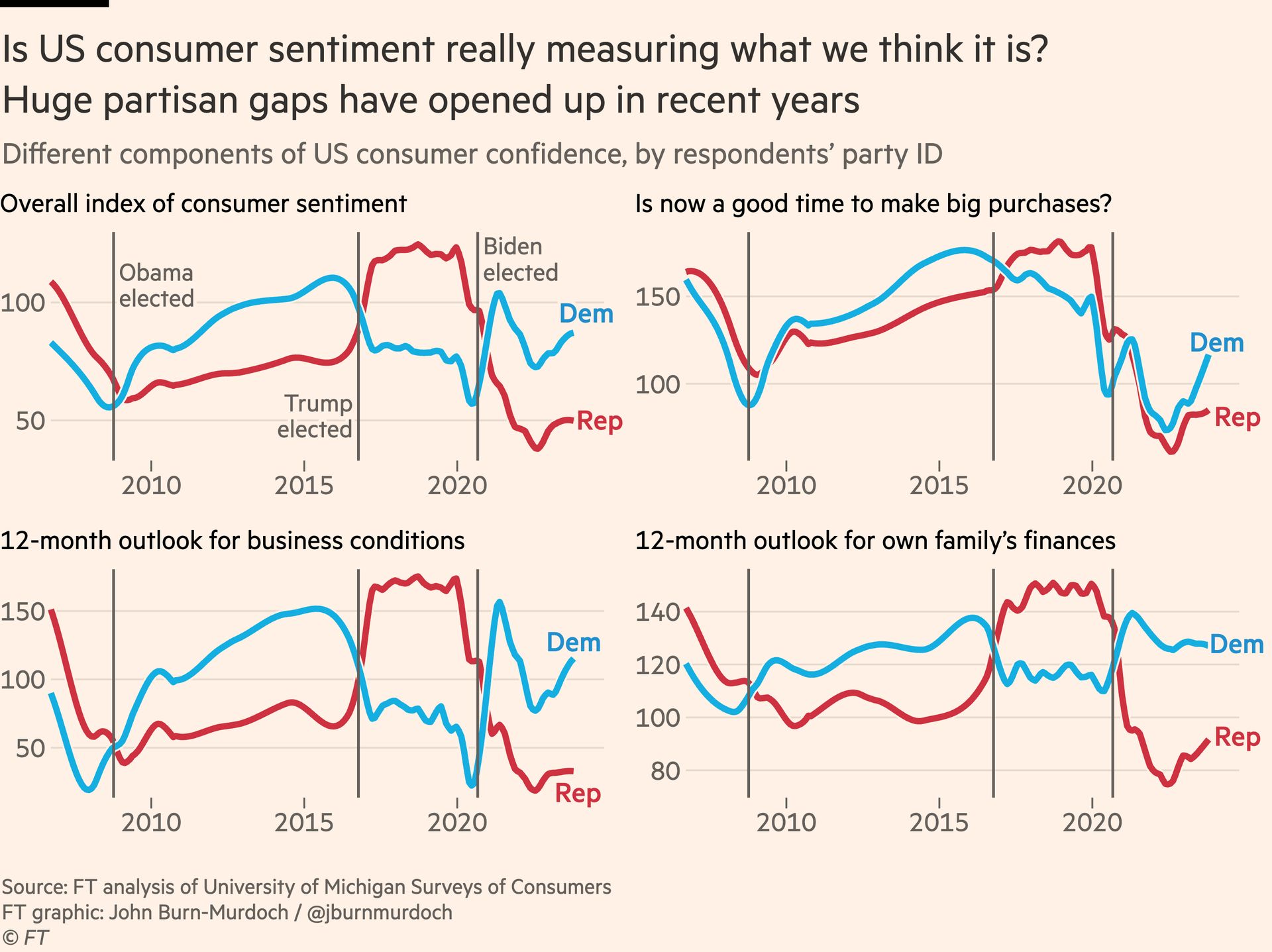

Political affiliation is also key to understanding how economic sentiments are separating from economic reality in the US. One question from the Michigan survey asks whether people think now is a good time to buy big household items. When the pandemic hit, Democrats and Republicans alike moved sharply towards “not a good time to buy”. But just months later, when Joe Biden won the presidential election — while Covid-19 still raged — Democrats suddenly declared conditions ripe for purchases of new fridge-freezers. Republicans did not.

It seems US consumer sentiment is becoming the latest victim of expressive responding, where people give incorrect answers to questions to signal wider tribal political or social affiliations. My advice: if you want to know what Americans really think of economic conditions, look at their spending patterns. Unlike cautious Europeans, US consumers are back on the pre-pandemic trendline and buying more stuff than ever.

john.burn-murdoch@ft.com, @jburnmurdoch

Survey details and other methodology

Survey of Americans’ views on economic trends: Focaldata carried out an online survey of 2,217 US adults between 25 and 27 November 2023. Respondents were weighted to be representative of the US adult population.

Actual vs expected consumer confidence analysis: expected consumer confidence was estimated using a set of linear regression models which which established the statistical association between monthly consumer confidence and a range of economic indicators between 1988 and 2019 for each country. Those models were then used to predict what consumer confidence would have been for each month in each country since January 2020 had those same statistical relationships held true.